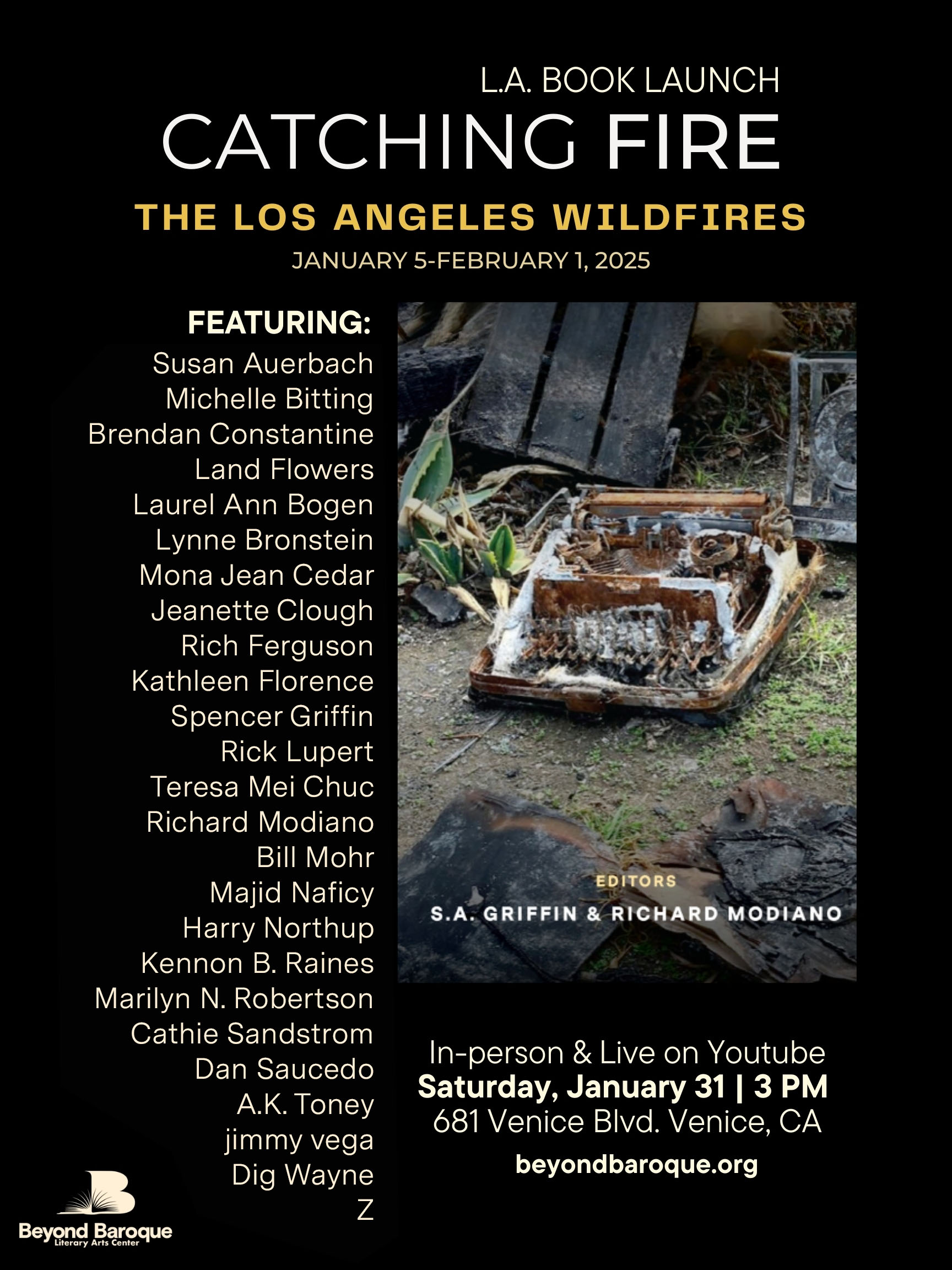

Please join me in supporting this book project, edited by S.A. Griffin and Richard Modiano, which has already raised through its sales a couple of hundred dollars on behalf of two recovery efforts.

Please join me in supporting this book project, edited by S.A. Griffin and Richard Modiano, which has already raised through its sales a couple of hundred dollars on behalf of two recovery efforts.

I have heard myself referred to as a “local” poet, a phrase that almost implicitly is meant to diminish the status of any artist or poet. Of course, I am hardly the only one besmirched with that term. I remember giving a talk at the Getty Research Institute in the fall of 1996 about the poets of Venice West and being challenged about the value of their insularity. “Who wants to be local?” Michael Roth asked me in front of a roomful of professors who were known for their scholarship on the city of Los Angeles.

At the time, I didn’t have an answer that adequately provided an escape hatch from my seeming intellectual provinciality. The point of the year-long seminar I was part of for a few months was to examine Los Angeles as a primary instance of what Peter Schjeldahl called a “transmission city,” a status long accorded New York, Paris, and London. The culture industry, with its global capacity to replicate hypnotic cinematic images, made readers of literary magazines with circulations of less a thousand people seem utterly irrelevant. That poets wanted to generate a gift exchange economy in direct opposition to the corporate seizure of cultural capital was regarded as too confined to be a serious strategy. Such an evaluation had consequences: a person sitting by herself, and reading a book published by Red Hill Press or Bombshelter Press or Momentum Press or Little Caesar Press or rare avis press or Mudborn Press was not endowed with any sliver of literary enfranchisement; in the 1970s, and yet… (yes, let’s pause here…) and yet it was poetry published by dozens of “local” small presses around the country that largely set in motion the multiculturalism that eventually aroused demands known as DEI. The fact that the backlash has been so ferocious in the past decade only shows that the “local” efforts of small presses and independent arts organizations (including Beyond Baroque, the Woman’s Building; the World Stage; and Tia Chucha) have been more than coterie efforts. Their antagonism toward centralized control of culture has earned its place as a form of pragmatic resistance.

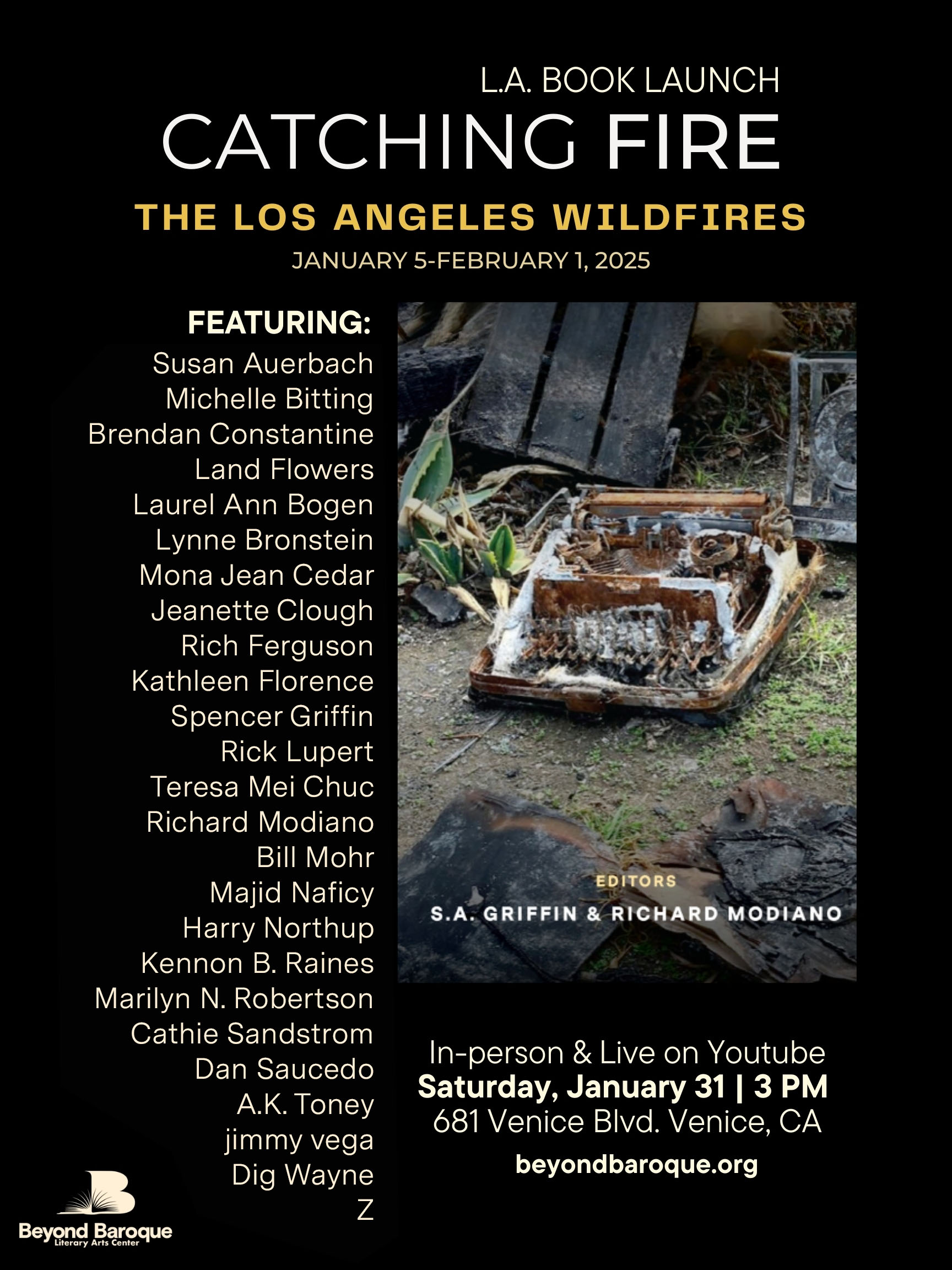

In particular, I would like today to point to an example of a publishing project launched by Harry Northup and Holly Prado that is still at work: Cahuenga Press. While subsequent collectives, such as What Books, have emerged and made an enormous contribution to a vivacious literary ecosystem imbued with nektonic energy, Cahuenga has distinguished itself with a series of volumes that directly confront the issue of being “local.”

Here is an early flyer. As briefly as I was a working contributor to this project, it remains one of the efforts I am most proud to have helped get underway.

On Sunday afternoon, December 7, 2025, Los Angeles area poets gathered at Beyond Baroque to read some of Cathy Colman’s poems. Colman was educated at San Francisco State University and she received her M.A. degree there in the mid-1970s after studying with Stan Rice. The poems in her M.A. these were already mature, memorable pieces of work and were far more substantial than one might expect of a person at her age.

Colman’s first book, BORROWED DRESS, did not appear until she was 40 years old, however, when her manuscript won the Felix Pollak prize from the University of Wisconsin Press. The book was popular enough soon after its publication that it made the Los Angeles Times bestseller list. Her poems were also gathered in two other collections, BEAUTY’S TATTOO (Tebot Bach) and TIME CRUNCH (What Books). Some of the magazines her work appeared in included Colorado Review, Ploughshares, The Gettysburg Review, and Plume. Her poems were also translated into Italian, Russian, and Croatian.

CATHY COLMAN

June 16, 1951 – April 30, 2025

BEYOND BAROQUE’S RECORDING OF THIS MEMORIAL EVENT:

(THE PROGRAM ON THE VIDEO DOES NOT BEGIN UNTIL ABOUT 17:17, so simply guide the red button to that point and Elena Karina Byrne will appear on the screen as one of the prime organizers of the event.)

I had hoped to attend, but I am no longer able to make long trips around Los Angeles two days in a row anymore. I had been at both DTLA and Beyond Baroque the day before, and traffic had been exhausting. Everyone at the Beyond Baroque event had spent at least an hour and a half getting to the event from where they lived.

The poem I had planned to read, if I could have attended as originally intended, was “While Deuterium and Tritium Spread,” which begins with an image from the 1950’s Cold War:

through animal and mineral, braiding

through my hair,

throwing open the window to the sky’s

cracked plate

of oysters and pearls, as

the clouds’ gold isotopes sail

through middle air’s

muddle, I can smell the wet pavement

from childhood rain

The poem ends with the kind of understatement that makes a theater script the most tantalizing form of imaginative literature. “the future waits offstage.” One feels the tremor of an haunting cue about to be spoken, and the effort it takes stay calm even as one knows that this Vesuvius will have a tsunami of lava that will obliterate almost all life on the planet.

Many of the poets who spoke at this event had known Cathy for years and spend considerable time with her or had studied at UCLA Extension with her or in private workshops, but I had hardly known her. I recollect once talking with her in the lobby of Beyond Baroque for about five minutes. Only afterwards did I revisit Suzanne Lummis’s WIDE AWAKE anthology and realize that Colman was inexplicably not in that collection, which came out in 2015. Colman was in Lummis’s most recent anthology, however, POETRY GOES TO THE MOVIES. with a two-page, three-part poem, dedicated to Chantal Akerman, entitled “News from Home.”

Colman’s metaphorical dexterity was on full display in the poems that her friends chose to read. One in particular stood out: “Happiness is a houseguest with an amiable smile after using all of the hot water to take a shower.” I don’t have the poem that image is from so that I can quote it exactly or with line-breaks, but I’ve not often encountered such a droll assessment of the motive and opportunity of happiness’s role in our lives.

Listening to Colman’s poems being read by her friends, nevertheless, will help assuage the sudden loss of yet another outstanding poet in Los Angeles.

Many thanks go out to Leslie Campbell and Elena Karina Byrne for making this event happen.

“o po-ets, you should getta job.” — Charles Olson

And if no one will pay you more than minimum wage, why not just set yourself for hire?

Meet the Long Beach typewriter poet helping strangers navigate heartbreak

As a thought experiment, imagine the Venice Boardwalk with fifty such individuals as Nico Patino offering to write a poem for anyone who stopped and requested one. It’s probably the case that Patino would get more requests than many of the other poets. There are several conjectures I could offer about why Patino would attract more passersby, but all of them involve trust. It’s not that easy to write a poem that doesn’t judge the subject of the poem with words “not untrue and not unkind.” With that talent at work, Patino has become the founder of “The Predisposed School of Poetry.” I don’t mean the title of this school in any way to disparage Mr. Patino. In fact, I hope he pounds out a short statement along the lines of O’Hara’s “Personism” that he will attach to his first self-published collection.

I cannot help but admire him.

Friday, December 5, 2025

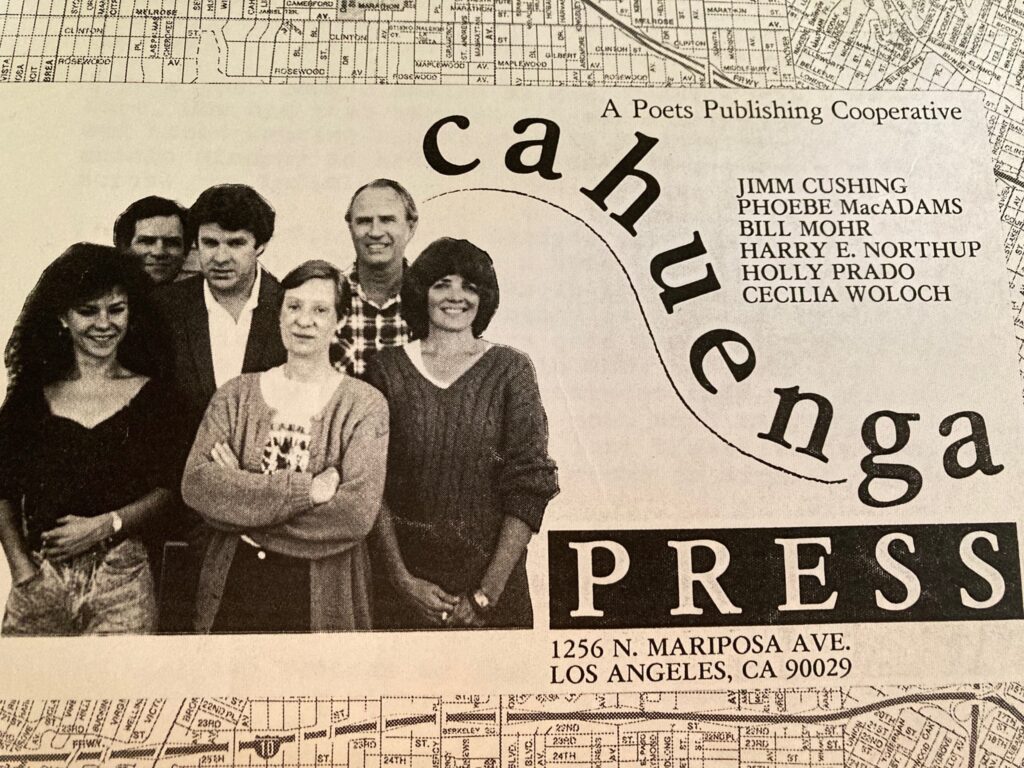

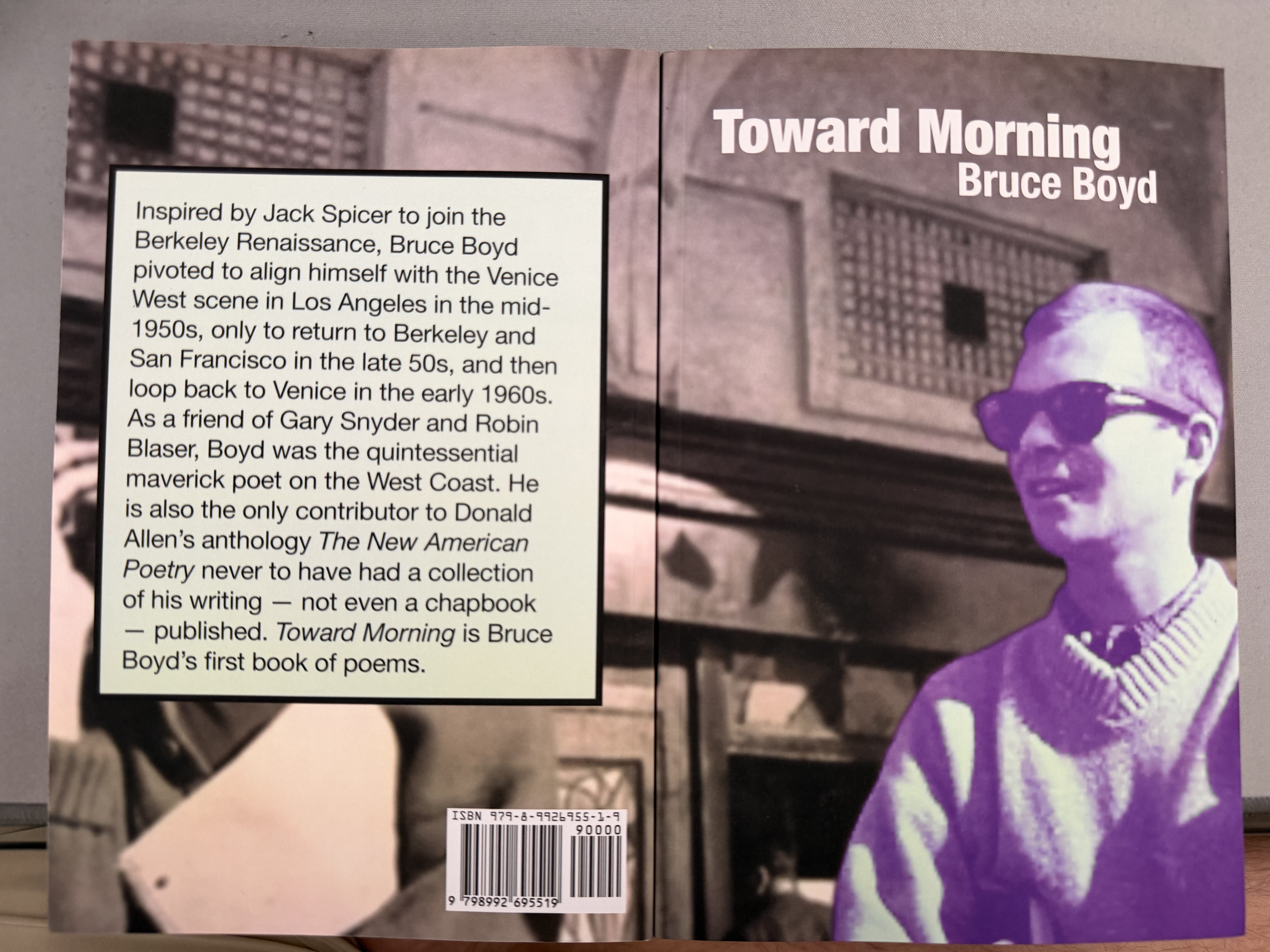

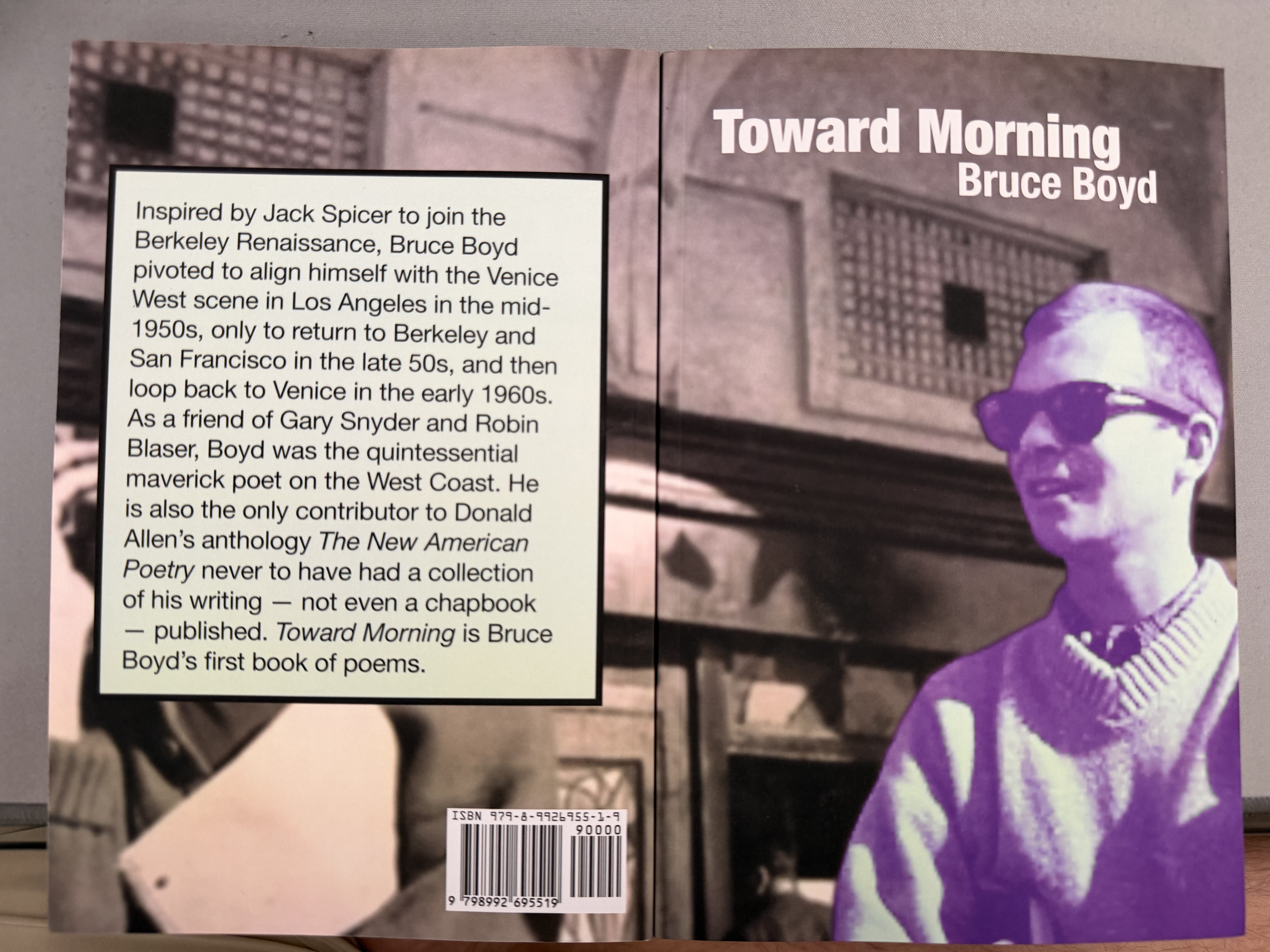

Inspired by Jack Spicer to join the Berkeley Renaissance in the early 1950s, Bruce Boyd pivoted to align himself with the nice West scene in Los Angeles in the mid-1950s, only to return to Berkeley and San Francisco in the late 1950s, and then look back to Venice in the early 1960s. As a friend of both Gary Snyder and Robin Blaser, Boyd was the quintessential maverick poet on the West Coast. He is also the ONLY contributor to Donald Allen’s canonical anthology THE NEW AMERICAN POETRY (Grove Press, 1960) never to have had a collection of his writing — not even a chapbook — published. TOWARD MORNING is Bruce Boyd’s first book of poems.

Boyd was born in San Francisco in 1928 and graduated from the University of California, Berkeley with a B.A. in philosophy. None of the letters written by Snyder, Blaser, or Spicer to Boyd have survived, but Boyd’s letters to those poets can be found in their archives. In addition, a considerable number of copies of letters by Donald Allen to Boyd can be found in Donald Allen’s archive at the University of California, San Diego’s Archive for New Poetry.

Boyd’s poems appeared in such magazines as Evergreen Review, Yugen, The Floating Bear, and J: A Magazine of Poetry.

Bill Mohr will read with Dennis Phillips and Jessie McCarty at Beyond Baroque, on Saturday, December 6, 2025, at 2:00 p.m. to celebrate the launch of Paul Vangelisti’s Magra Books.

Dennis Phillips / The Cartographer’s Lament

Bill Mohr (editor) / TOWARD MORNING: Selected Poems by Bruce Body

Jessie McCarty / Pretty Punks (forthcoming in the spring 2026)

Many thanks go out to Sean Pessin and Mckensi Bond for their assistance in bringing Bruce Boyd’s book into circulation.

Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center

681 Venice Blvd.

Venice, California

90291

(310) 822-3006

Almost forty years ago, Ron Silliman’s anthology IN THE AMERICAN TREE served as a definitive punctuation mark in the emergence of Language poetry. Was it a period or a semi-colon in marking the end of the “first” portion of the practices of writers who were almost uniformly on either the West or the East Coast? In any case, one of the poets whose work in Silliman’s anthology most impressed me was Tina Darragh, whose contribution was entitled “Raymond Chandler’s Sentence.” To my knowledge, it has not been reprinted in any other anthology, even though it is one of the best poems I’ve ever read. I still remember where I was sitting when I read it for the first time, as well as my most recent encounter. It’s a visibly embedded text in the midden of my lifetime of reading poems.

I spotted an obituary for her the other day and wondered yet again why so few people in Los Angeles have taken note of her passing. No doubt Doug Messerli and Diane Ward were the first to hear of it, and maybe then Harold Abramowitz. I know of no plans to honor her at Beyond Baroque, however.

Here is the biographical note that George Washington University has posted for her literary archive at that institution’s library.

“Tina Darragh (November 21, 1950 – November 18, 2025) was a poet and librarian. Born in Pittsburgh Pennsylvania, grew up in McDonald, Pennsylvania and moved to Washington D.C. to attend Trinity University. While at Trinity, Darragh became interested in writing poetry and met many other local writers. Darragh would meet up with these writers at Mass Transit and later at Folio, local community bookshops. She worked with Some of Us Press (S.O.U.P).

Some of the poets Darragh knew as fellow writers as well as friends included Diane Ward, Joan Retallack, Tim Dlugos, Bruce Andrews, Terrence Winch, Beth Joselow, Lynne Dryer, Doug Lang, Douglas Messerli Welt and P. Inman. These poets and others came together to form the east coast branch of the Language group of poetry. This style of poetry emphasizes the reader’s role in the work. Darragh spent much of her professional life as a librarian working at Georgetown Univeristy firt in the National Reference Center for Bioethics Literature and later as a more general refernce librarian.

She and the poet P. Inman were married and have a son Jack and two grandchildren.

Tina Darragh died November 18, 2025 in Washignton D.C.”

Her cohort of exuberant comrades includes an all-star team of her generation’s most judicious members of a poetic avant-garde: Diane Ward, Joan Retallack, Tim Dlugos, Bruce Andrews, Terrence Winch, Beth Joselow, Lynne Dryer, Doug Lang, Douglas Messerli Welt and P. Inman. I repeat the list because I think readers tend to skim such lists without reflecting on how different these poets are from each other. Anyone who can’t detect how different they are simply isn’t willing to put in the work that poetry demands of those who would claim to be its advocate.

Here is a link to the notice of her passing posted in JACKET2:

https://jacket2.org/commentary/tina-darragh-obit

And here is an interview with her:

https://www.dcpoetry.com/history/darragh

My condolences go to the poet, Peter Inman, her husband, who also had admirable work in IN THE AMERICAN TREE and Tina’s and Peter’s family.

Saturday, December 6, 2025

2 p.m.

Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center

681 Venice Blvd.

Venice, CA 90291

Bruce Boyd was born in 1928 and was close friends with Jack Spicer, Robin Blaser, Gary Snyder, and Stuart Z. Perkoff. He also corresponded at length with Donald Allen, who included Boyd in his canonical anthology, THE NEW AMERICAN POETRY (Grove Press, 1960).

Yet Boyd never had a book of his poems published. Not even a sixteen-page chapbook came out with his name on the title page!

After years of effort on my part, I found a publisher for an initial collection of Boyd’s poems. Paul Vangelisti, who published two Venice West poets fifty years ago through his Red Hill Press, now adds a third poet associated with Venice West to his publishing credits. Magra Books has just issued TOWARD MORNING, Bruce Boyd’s first book of poems!

I will be at Beyond Baroque this coming Saturday, at 2 p.m., to celebrate this accomplishment along with Dennis Phillips, L.A.’s most philosophically lyrical poet.

Please join us.

Soon after receiving my B.A. in theater arts from UCLA, I obtained a copy of Michael Horovitz’s CHILDREN OF ALBION: THE “UNDERGROUND POETRY OF GREAT BRITAIN” and found myself puzzled as to how these poets could be so invisible in the United States. While Horovitz’s anthology hardly proffered the experimental scope of Donald Allen’s THE NEW AMERICAN POETRY, it nevertheless alerted those whose only knowledge of British poetry was Hall-Pack-Simpson’s NEW POETS OF ENGLAND AND AMERICA that Great Britain was also simmering with non-academic poetry.

It turned out, though, that Horovitz’s anthology fell far short of giving a comprehensive account of how lively things were in Great Britain. The Beatles weren’t, in fact, the only thing that a port city in northern Great Britain a sense that it deserved far more respect for its cultural ferment than it had been receiving. Several young poets in Liverpool had gotten so much attention by 1967 that Penguin Books issued a volume entitled “The Mersey Scene,” a title that took advantage of the public’s familiarity with the main river that goes through Liverpool. Let’s be honest, here: Spenser and Blake, among many others, made the Thames River famous, but it took a pop music group to make the Mersey known world-wide. I haven’t yet found out the name of the person at Penguin Books who decided to give one of the volumes in its Penguin Modern Series of Poets a specific title. Before then, each volume, containing a substantial selection of work by three poets, was simply numbered in sequence. It was a brilliant move: eventually a half-million copies sold.

But marketing can only carry a product so far. Maybe someone in a bookstore might give the book a look of poems a look based on its title, but if the poems don’t keep their attention, it’s unlikely she or he will buy a copy. If Adrian Mitchell’s scathing critique is still relevant (“Most people don’t care about most poetry because most poetry doesn’t care about most people.”), then the Mersey Scene was an extraordinary exception. There is a kind of implicit Venn diagram ins Mitchell’s observation; what get overlooked is that there is a shaded in conjunction of those who do care about poetry because it enables them to care about themselves both as individuals and as a literate community with disparate values. If “care” means “nurture,” then poetry and its readers cultivate a mutual nourishment that amounts to a riparian ecology: the marshland of consciousness with all its rhizomatic inlets and outflows of self-pleasuring language.

Horovitz, however, did not include the three poets who made THE MERSEY SCENE such a success. It seems almost inexplicable that he would have left their poets out of a book that claimed to be a survey of “underground” poetry in Great Britain in the 1960s. The justification for their absence is confined to a single paragraph in a sixty-one page “Afterwords” in which Horovitz meanders from topic to topic in the manner of a tour guide on the magic bus of underground poetry: Look over to your left, there’s where the poetry festival was held; and up ahead, just between the boutique and the record store is a bookstore in which one bought copies of my magazine, New Departures, which the TLS called the most interesting things, etc., etc.” One gets a definite feeling that Horovitz is jealous of the fame that Brian Patten, Roger McGough, and Adrian Henri have accrued though their lively performances in Liverpool and their embrace of the cultural insurgency that was associated with the Beatles.

Adrian Henri was the first of the three to die. Sad to say, as far as I can tell, the only public notice in the United States about the death of British poet Brian Patten was in a weekly industry newsletter, Shelf-Awareness, dated October 6.

https://www.shelf-awareness.com/issue.html?issue=5078#m69127

For that matter, I have my doubts that his death registered at all with any of the people who are planning to attend the AWP conference in Baltimore in the spring of 2026. I wonder, in particular, how many professors in MFA programs in the United States could identify in any way Brian Patten and talk, off the cuff, about Patten’s emergence as a central poet of the Liverpool scene.

The discrepancy between the wide coverage that Patten’s death received in Great Britain and the almost total silence about his passing in the United States only confirms my sense of the arrogant provinciality of American poetry, convinced as it is of its imperial exceptionalism.

To find out why Brian Patten was so respected and admired in Great Britain, cut and paste these links into your browser:

https://www.theguardian.com/books/2025/sep/30/brian-patten-obituary

https://simonwarner.substack.com/p/obituary-7-brian-patten

I would add to these commentaries that what made Patten and his friends Adrian Henri and Roger McGough such an intriguing crew of poets is that their performance-oriented poetics arrived at just the right time to both contribute to the cultural upheaval of the 1960s and to take advantage of its comic populism.

Given the paucity of notice given to the passing of Brian Patten, it was a shock to see that the New York Times ran a lengthy obituary for an equally fine poet, Tony Harrison. If Patten wore the comic mask to hide his pain, Harrison thrust the tragic mask like a branding iron to buttocks of the ruling class. I often tell students that when Emerson said that a poem is a meter-making argument, he didn’t mean that the goal was to figure out an argument and parse it out in meter. He meant that the argument is so fiercely felt that the only way to keep it from spinning out of control is to use meter to subdue the writhing emotions recollected in exasperated tranquility.Harrison’s skill in using meter and rhyme is perhaps the most deft of any poet since Jonathan Swift, whose boiling point he shares as a point of honor. Harrison deserved his notice in the NYT, but the privileging of “serious” poets over (comically) serious poets once again makes me suspect that too many people in charge of cultural commentary don’t care if most people don’t care about most poetry.

NOTE: This blog entry, as with all the blog entries on billmohrpoet.com, is copyright by Bill Mohr, and is meant only for the edification of its readers to the extent that it might give them worthwhile insight into reading literature. My social and political commentary is meant to serve the same purpose in the public sphere of civic discourse. Any retention of this material in order to make use of it in training artificial intelligence in any manner whatsoever is an obnoxious appropriation of my labor. I am aiming this statement, in particular, directly at any people in China who might be operating webcrawlers.

In the past six months, for instance, here is a list of the countries in which people are engaging in some way with my blog:

Views

United States. 3,226

China. 2,567

United Kingdom. 180

Germany. 126

Canada. 89

Australia. 72

Belgium. 33

Chile. 32

Italy. 31

France. 27

I find it impossible to believe that there are four times as many people in China who are interested in my blog as there are in eight other countries, unless of course the purpose in China is to train LLM. If their courts want to call it “fair use,” don’t expect me to be generous when the ground shifts under you.

from LE MONDE:

La France commémore le 13-Novembre dans le recueillement et l’émotion, dix ans après : « Il y a un vide qui ne se comble pas »

RÉCIT

La France commémore le 13-Novembre dans le recueillement et l’émotion, dix ans après : « Il y a un vide qui ne se comble pas »

Du Stade de France au Bataclan, anonymes et officiels ont rendu hommage, jeudi, aux 132 morts dans les attentats de 2015. Place de la République, une cérémonie a réuni les Parisiens jusque tard dans la nuit

R.I.P. Nohemi Gonzalez.

Ms. Gonzalez was a student in her senior year at California State University, Long Beach, where I have taught since 2006. She was studying in France at the time of her murder. One hundred and thirty-one other people were murdered on that day, too.

Linda and I were at the airport that day, waiting to fly to France so that I could give a talk at a conference in Dijon, France. The two weeks Linda and I spent in France left us with memories that help us understand that people in the United States may have forgotten about what the French called “the events,” but why France has not.

Linda and I send our deeply felt condolences to all the people of France, whose company we were privileged to share at a time of extended national mourning.

“Self/not Selfie: An Exhibition of Self-Portraits

Golden West College Art Gallery

Fine Arts Building, Room 108

15751 Gothard Street

Huntington Beach, CA 92647

Gallery open Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, 10 a.m. to 2 p.m.

FINAL WEEK

This show just received a very glowing review by Kristine Schomaker in ART PLUS CAKE magazine.

https://www.artandcakela.com/post/self-portraits-as-existential-affirmations

This show includes work by Amy Runyen, The Giver (Graphite and watercolor); Nurit Avesar Acrylic; Sarah Soward, Leap Before Looking (2025) Mixed media on canvas; Valentina Aproda Maurer, Camouflage (2), 2021, Digital inkjet print; Laura Meyer, Self Portrait, Crying; 2023, oil on canvas; Marina Claire, When Every Particle of Dust Breathes Forth Its Joy, 2025, Oil on wooden panel; Phyllis Chumley Martinez, Can’t Live in Daddy’s Playhouse, 2019, Oil on Canvas; Kerri Sabine-Wolf, Unraveling, 2025. Oil, Graphite, and Charcoald on Canvas; and Linda Fry, Self-Portrait, 2025, watercolor.